If you are not aware, I recently returned from a 16 day deployment

to Puerto Rico. The Caribbean was devastated by Hurricanes Irma and Maria.

Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands were direct hits, and as a result, were in devastating

states of emergency. All of the islands lost power, fresh water was cut off,

roads and transportation systems were destroyed, communication ability was completely

eliminated, and access to health care was erased. First of all, after being immersed

in this atmosphere, all I can say is to don't believe the mainstream media.

They may be accurate on some accounts, but they make mountains out of mole

hills often. Yes, the devastation was probably as bad as they were saying it

was, but NO, the response and efforts to help the residents was not horrible…

it was alive and very active.

I am a Commissioned Corps Officer for the United States Public

Health Service. As such, we are considered military and one of the seven

uniformed branches. We are 24/7 deployable. We don't fight battles, we fight disease

and disasters on deployments. If we aren’t deployed, we are stationed across

the country protecting, promoting, and advancing the health and safety of our

Nation. I am on a National Incident Response Team. What that means is that we

are considered Tier 1, and the first to typically be called to deploy. We have

advanced training and requirements beyond the basic Commissioned Corps officer.

This often means we deploy as a member of the Incident Command Center in the

heart of the disaster.

Like I said in my previous post, I was on call for deployment during my moose

hunt (although I was mission critical to the hospital because I was covering for other officers that were potentially deploying); I had to stay connected and available. Luckily, I wasn’t called in off the hunt, however, a couple days after returning, I was notified of my need

to assist in Puerto Rico. I knew the call was likely coming because my mission critical status was expiring, so I had a couple

days to get prepared. I packed for the most extreme conditions. Luckily for me,

I’m a back-country hunter so I have all the needed gear and survival items to

live in an austere environment… I’m just not used to functioning in a hot

environment. We were pretty much left to guess what we needed to take with us

though (because you couldn’t really get something there that you forgot to

take). For the most part, I took everything that was truly needed. Of course, I

learned what best to take after I got there, but I’m better prepared for a

similar environment next time.

This deployment was not a typical deployment. The destruction was

greater than any disaster our government has dealt with, the demand for people

and resources was the highest is has ever been, the location was unique due to

being an island in the Caribbean, the politics were odd since Puerto Rico

basically functions independent of the United States, and the baseline

infrastructure and health care system was questionably unacceptable prior to the

hurricanes striking. All of these issues compounded on each other and made

every step of the deployment and recovery efforts even more difficult… this was

uncharted territory.

Being in Quality, I am acutely aware of inefficient processes,

needs for performance improvement, and identifying system issues. Again, the sheer

magnitude of everything made many steps in the deployment process difficult to

execute perfectly. With that said, the start of the deployment was a little

frustrating for me. I was scheduled to deploy on a Thursday, however, Wednesday

afternoon, I received my itinerary to fly out Wednesday night. I was eventually

able to get this changed to the correct date. I departed on Thursday morning,

but when I was in the airport, I received an email stating that my itinerary

was delayed until it could be appropriately approved. I was already checked in,

so I figured this wasn’t possible to delay… and I was right. I flew the entire

day, updating the proper individuals of my location changes. When I arrived in

Atlanta around 11 (Atlanta is where everyone stages prior to flying into and

out of Puerto Rico), I headed to the pre-specified meeting area. To my

surprise, there was nobody there to meet me. After waiting for 30 minutes, I called

the phone numbers I was given in case I needed help. I got in touch with a guy

who said to sit tight while he figured out how to get me. I then waited another

30 minutes before I called him back asking about an update. He said that no one

was available to get me and that I needed to take a cab to a specified hotel,

check in as PHS, and sleep in the next day. So I did.

I got up early the next morning to discover that nothing really

started moving until 8AM. At 8, I asked officers I passed where I should go and

I eventually found the conference room that was making flight arrangements. I

gave them all my information, got tested for respirators, and was updated on

the conditions in Puerto Rico. Flights were very difficult to get in or out of

Puerto Rico. There was about 150 of us waiting in Atlanta to get to Puerto

Rico. They were trying to charter a plane that would take responders back and

forth on a consistent basis, but that contract wasn’t solidified yet. They would

try to get us on a plane with space as it became available, so we were told to

be ready to leave with a 30 min notice. Until then, we were instructed to

“relax” before the hard work began. This is when I got a true sense of what

people mean by a HURRY UP AND WAIT mindset for deployments. I was hurriedly put

on a plane to get to Atlanta, only to find out I may be sitting there, on call

for five days or so until I could get to Puerto Rico.

It’s hard for me to sit around, so I looked for ways I could help.

I came across an old acquaintance who turned out to be overseeing the Service

Access Team there in Atlanta. Their job was to receive dialysis patients from

the islands and make sure they got the care and hospitality they needed…

basically case management with a daily living component. They were thrilled to

have me as help because they were apparently short staffed. In short, I was

tasked with temporarily helping with oversight of the Federal Coordination

Center, where we received the patients at a hanger on the local military base.

We would coordinate their arrival, assess their situation, medically screen

them, gather their belongings, get them what they need, and provide

transportation to their temporary living situation with further instructions on

how to get the care they were sent here to receive. It was quite the experience

and I’m glad I was able to lend a hand.

At about 11PM on Saturday night, we were told that we had to be

ready to fly at 6AM the next morning. They were able to get a bunch of seats on

a FEMA flight that was heading down in the morning.

The next morning came and to our surprise, there wasn’t a bus at

the hotel to pick us up. Apparently, the staging hotel switched and we were

forgotten in the switch. Luckily, a logistics guy saw us waiting and he was

headed to the other hotel. We bummed a ride from him and caught up with where

we were supposed to go. They put us on a bus stuffed with a couple Disaster

Medical Assistance Teams (DMAT). We ended up waiting there for three hours

until we finally boarder our plane.

Lucky for me, I got an exit row! The flight was only 3.5 hours

(nothing compared to flying from Alaska). At this point, I regretted not having

a window seat too. To be honest, I was surprised to see San Juan from above in

such good shape. Growing up in Iowa, I know what the aftermath of a Tornado

looks like, and for some reason, that is what I expected here. That was not the

case. In fact, most buildings didn’t have a single broken window. It wasn’t

until I landed that I realized this wasn’t indicative of the real situation at

hand… and the newer buildings are the ones that escaped most of the damage.

We deplaned and I immediately noticed the smell there. It was an

old, musty smell that I would soon get used to and forget about. Of course, it

was hot. It was also very humid. Just getting back from camping in freezing

temperatures, this was quite the uncomfortable change. I also noticed the

damage to many planes, hangers, and especially all the surrounding trees. Most

trees were knocked over and absolutely none of them had leaves or fruit. After

all the bags were taken off the plane, it started raining a little bit. Lucky

for me, I had an umbrella in my backpack; others just stood under the plane

wing. We stood on the tarmac for a while waiting for direction. It was clear

our command center did not expect us at the time we arrived. A handful of vans

and buses eventually showed up to take us to the convention center. I was

surprised to see that we had an escort of law enforcement that would stop

traffic for us and make sure we were escorted safely and quickly.

After about 15 minutes, we arrived at the conference center. This

place was HUGE! It was packed with thousands of people from all over… military,

humanitarian people, heavily armed security, stranded residents, responders,

powerful politicians, and more. There were multiple loading docks set up with

hundreds of cots for responder barracks. Hundreds of meetings rooms filled all

three floors, each completely packed with one group or another contributing toward

the relief effort. Armed guards with automatic rifles across their chests were

at every access point and checking IDs. I have no idea how the convention

center was able to keep up with maintaining that place well enough to

accommodate so many people, for so long, every hour of the day. But thank

goodness for this building still being in one piece because it was critical to

the centralization and coordination of the response effort.

Once we got in the conference center, there was more confusion. We

got off the buses and no one really knew where to go or what to do. We found

our way to the Incident Response Coordination Team (IRCT) room where Health and

Human Services had the Command Center set up. It was clear they weren’t really

expecting us. We didn’t know who to talk to or what to expect. We asked around

and nobody really took us in and helped us make sure we got what we needed or

where we needed to go. We eventually talked to enough people to figure out what

positions we would hold in IRCT and where we would stay for the night (luckily,

they had a hotel room available for each of the new IRCT personnel).

We were told to go get our bags and to wait out front for a van to

get us. After trying to locate our bags for a while, we took our stuff and went

to the front of the building to wait. We ended up waiting close to three hours

for a shuttle to take us to the hotel. At about 8PM, we were finally picked up.

Unfortunately, the guy didn’t know how to get to the hotel and tried to get

directions from our phones (which of course didn’t work). The combination of

possibly being lost in Puerto Rico, driving on roads with no street or traffic

lights, dodging fallen debris, and avoiding the countless bad drivers… we

weren’t feeling too safe.

We finally made it to our hotel. Once we got there, we met a guy

from IRCT who assigned us a room. When I got to my room, I immediately noticed

it was already used. There was a trunk of gear in the room and the towels were

used, but there was no luggage or evidence it was being slept in. After

returning to the front desk to get my room situation figured out, I was told

that all the rooms we had reserved were taken. I was told I may have to go to a

different hotel or back to the Convention Center to sleep on a cot. Luckily,

they worked out a deal and I was placed on the top floor, in a penthouse room

(which wasn’t anything special compared to the other rooms… perhaps better

access to water, that leaked from the ceiling).

I finally set my bags down at about 11PM. I still had to train for

my position in IRCT tomorrow, so I called my trainer to let them know I was

finally settled. I met her in the lobby and we discussed my responsibilities.

The directions weren’t very clear, and not being in IRCT at the time muddied

the waters a little bit. Regardless, I knew that on-the-job training would be

the most beneficial anyway, but I still absorbed as much as I could… despite

the long day of travel.

Our training session took about an hour and I was back in my room

by midnight. I quickly unpacked everything, showered, and hit the hay for an

early morning and my first day in IRCT. (Yes… I was shocked to have a warm

shower. Apparently, the hotel had a generator that powered the whole place.

They also had “clean” water, although our safety officer recommended nobody

drink it.)

The shuttle left the hotel at 6:15 and 6:45 every day. I woke up

early enough to eat the breakfast buffet at 6:00. It was rather simple (eggs,

toast, bacon, and potatoes), but I was just happy to not have to eat MREs. Oh,

also, I now have a new favorite juice… Passion fruit juice! That stuff is

ridiculously good!

I jumped on the early shuttle and got to IRCT a little before 7AM.

Everyone got settled and I briefly spoke with my Section Chief about what I

needed for my position as the Unit Cost Lead. Apparently, I was placed in this

position because they caught wind of how well I was with Microsoft Excel. Typically,

my position is within Operations as a Group Supervisor. Unfortunately, Group

Supervisors were not really being utilized yet at this deployment due to the large

number of teams in the field and their constant movement. If group supervisors

were to be utilized like normal, we would have needed about 15 of them to match

with field teams. As a result, I was stuck inside for most of the deployment,

helping keep everyone organized, efficient, and accountable (or at least I

tried).

The first day in IRCT for me was rough. I can only imagine how

similar my experience was in IRCT to what others experienced. I had no idea

what I was doing really, despite the attempted midnight training session by

someone who didn’t even understand Excel. I tried getting clarification on

exactly what I needed to do and how I could help, but my section chief was too

busy the entire day to even sit down and talk to me about expectations. Regardless,

I found work (mostly Excel related) and extended an offer to help wherever I

could. I was actually placed at the front of IRCT, and everyone that came into

the room talked with me first (thinking I was placed there to great people,

like a glorified receptionist) expecting me to know the answers to where they

should go or who they should talk to. Although it wasn’t my responsibility, I

quickly learned everyone’s name in IRCT and what their role was… so I could

answer questions like, “I feel sick, who can I talk to?”, “We were flagged down

by people needing medication and water, who do I give this request to?”, “I

control all the helicopters in the air and need to ask IRCT some questions.”,

“Will you please give ___ a message?”, “I represent the attorney general and he

wants to know when we can expect bodies to be moved.”, “Have you seen Mojo?”,

“Where can our team get water?”, and MANY more questions. Really, my official

job was to track and monitor all costs associated with the deployment, as well

as coordinating the arrival and demobilization (return home) of responders. There

were also many duties as assigned.

Basically, once I got assigned my position and I realized I wasn’t

leaving IRCT, the hours, shifts (at least 12 hours from 7-7), and days started

to blur together. The cycle of waking up, eating breakfast, going to the

Convention Center, working in IRCT all day, heading to the hotel, eating

dinner, doing my day job work, talking with Danielle and Ashton, and then going

to bed became normal.

** I tried come up with a good way to organize the remainder of my

thoughts and experiences. I don’t remember what happened on which day and in

what kind of chronological order. As a result, I’m going to brain dump

everything and separate it all by topic. Feel free to pick and choose which one

you care to read about. **

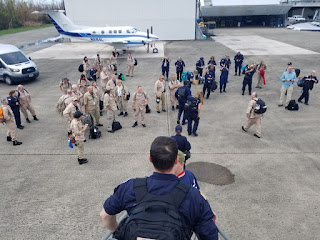

Inbound/ Outbound Flights

I was routinely in charge of organizing the incoming and outgoing

charter flights, and making sure appropriate individuals arrived and left on

those flights. A part of that responsibility was being at the airport on the

days our charter flights arrived and left. Basically, I was in charge of making

sure the confusion that happened with me when I arrived, didn’t happen to

others.

I coordinated with our transportation lead and security escorts to

make sure we had the right people in the right places before we went anywhere.

Each charter flight had close to 150 people coming in and going out of Puerto

Rico. We had to take role call and check off everyone. It was a very hot and

chaotic process being out on the tarmac with 150 people coming off the plane,

gathering their bags, and then having 150 people load their bags and then getting

on the plane. I eventually developed a process that consisted of bus

assignments, roll call orders, and double checks that resulted in a smooth

accountability process.

We eventually learned to not fill every seat on the charter plane.

We learned the hard way after an occurrence where the pilot would not fly until

we lost weight on the plane. This resulted in randomly selecting individuals to

get off the plane (keep in the mind the charter only flew twice a week) and the

pilot randomly selecting bags to not fly as well. This meant people were not

flying that should have been. The people that stayed didn’t have their bags and

bags arrived without people, also, people arrived without bags because a

handful were randomly selected to stay in order to make weight.

We had a couple responders who got separated from their bags and

had to hurriedly be sent to the Virgin Islands. They were told by IRCT that

they would get their bags as soon as possible, but it took ELEVEN DAYS to

reunite them with their bags. Can you imagine living out of your carry on that

is supposed to have enough stuff to last you 24 hours? Now try doing it on a

destroyed island with no access to buy any of your needed items.

Wrong Position

A couple days into the Puerto Rico IRCT duties, my section chief

confirmed my position and discovered that I was not supposed to be doing what I

was assigned. I was supposed to be a part of operations and placed as a

supervisor of a field medical team. After the two section chiefs talked, they

decided to leave everything the way it was, and not switch positions.

Quality Improvement

My day job focuses on quality and performance improvement. It was

difficult for me to see so many process drops and inefficiencies. I took pride

in improving many processes and making them more efficient while I was in IRCT,

but there was one process that backfired. I won’t go into too much detail or

pointing fingers, but I actually got in trouble for attempting to improve a

process.

I witnessed countless people requesting to be demobilized home on

a certain date in the future. When that date came, they weren’t on the fly list

due to them not being recorded appropriately or being forgotten, mostly as a

result of 20 different ways a demobilization date could be requested. I felt

bad for these individuals and it appeared the broken process was destined to

continue. As a result, I created a master list of everyone’s desired

demobilization date (Excel powered of course). It was a great collection of

data, but unfortunately, duplicated an already existing inefficient process

that someone else was already overseeing. When it was discovered that multiple lists

existed (including mine), I was scolded and told to stop updating mine, and

that the others would be used as reference. Unfortunately, I know for a fact

that there were names and dates on my list that did not make the other lists

when I was told to cease.

The irony in this is that a couple days later, IRCT Command

criticized the current demobilization date collection and awareness process and

requested it be revamped, more accurate, and hassle free. I’m not sure what was

done to ensure this.

Food and Water

I was fully expecting to eat MREs for every meal while I was on

the island. If you don’t know what an MRE is, it’s a Meal Ready to Eat (MRE).

They are made to last forever, come in a pouch packed with a couple thousand

calories, contain a way to warm your food, and are specifically made for moving

military. I’m happy to say I didn’t eat a single MRE.

Food was readily available (although variety and depth was

unsurprisingly lacking). The convention center served three meals a day. There

were two concession stand type areas where they served the same food, one on

the third floor ($12) and one on the first floor ($5). The top floor gave you

larger portions and included more items in the price. The hotel had a

restaurant that served breakfast and dinner. There was also a pizza place

across from the hotel (ate there one night) and an Asian place next door to the

hotel (ate there about six times; BEST mandarin chicken I have ever had). I had

a ton of snacks and food that I brought from home too, so I was well off.

Water was available. Again, I was prepared to be thirsty. I

actually brought water treatment tabs and hydration packs that were not needed.

The island had no way to test the city water, but they claimed it was safe to

drink by the time we got down there. No tests = no recommendation.

Bottled water was our source of fluid. There were times when it

was scarce and hard to come by in the convention center, but that didn’t last

too long. To top it off, the hotel gave me two small bottles with every

cleaning.

Communications

AT&T was the service to have on the island. All Verizon

service went down for a while until AT&T said that everyone could use their

towers. This initially limited it to five-minute calls, but they soon lifted

that as well. Very few areas in Puerto Rico actually had cell service

available. In fact, if you drove through San Juan, you would see a shockingly

high number of cars pulled over on the side of the road in many places. People

were driving into town to find coverage and use their cell phones. Since we

have Verizon, it was difficult to send or receive texts or calls. I know many

of mine failed and I didn’t receive a handful from other people (Sorry for not

calling you Mom).

Most field teams were given a satellite phone. You would think

that these would work perfectly anywhere… wrong. We actually had extreme

difficulty getting the sat phones and G2s to work consistently.

Along the same lines as communication, Spanish was the language to

know. I can speak and understand French, and that didn’t help during this

deployment (I now regret not choosing Spanish growing up). Most residents know

both Spanish and English, but there were a large number that only knew Spanish.

This was detrimental to me being as helpful as others outside of IRCT.

Fortunate/ Lucky/

Undeserving of Accommodations

I felt an immense amount of guilt while in Puerto Rico. Here I

was, in IRCT to help with the recovery effort of residents that lost everything

in the hurricanes, have unmet medical needs, no place to stay, nothing to eat

or drink, cannot escape the heat and weather, unable to get basic living items,

and have no way to communicate beyond the distance their voice can carry.

Meanwhile, I’m in an air conditioned building, sleeping in a clean bed with a

clean body every night, able to get food and water when I want it, and have the

ability to connect to anyone via Internet or cell phone. I couldn’t help

feeling ashamed or a need to also experience the hardship of the people I was

there to help.

Our hotel was right next door to a grocery store. This grocery

store opened at 7AM every day. Every morning at 6AM, we could see a huge line

of people that wrapped around the block, waiting to get in to eat at their

deli, hoping to fill their water containers, and wanting to pick through newly

stocked items.

Many of our responders were also placed in tough situations,

however, comfort of the responders really depended on where they got placed in

the field. Some stayed on cruise ships that were fully staffed (multiple ones

arrived as the deployment extended, due to hotels being sold out), some stayed

in beach front resorts, while others had to camp in unconditioned tents, or

even sleep in hospitals. Accommodations were extremely variable.

Political Leaders

There were many political and high-ranking officials at the

convention center. President Trump visited the island but he did not visit the

convention center. Vice President Pence did visit the convention center, and

briefly spoke as well. I did not get to hear his speech as we were dealing with

a tight deadline to get responders where they were needed.

The Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) was

present for most of the time I was in IRCT. This guy is pretty much every

responder’s ultimate boss, so his presence was a big deal. We saw him daily.

I got to meet the current Surgeon General as well, Dr. Jerome

Adams. He was on the island for about a week and in and out of IRCT often. At

one point, I had the opportunity to sit down and talk with him one on one about

everything from our families to the current situation in Puerto Rico and how

awesome Alaska is. The next day I got him to pose for a picture with myself and

a fellow NIST member, CDR Verni. To top it off, Dr. Adams was also staying in

our hotel and one night I saw him wondering around the restaurant by himself. I

was there with a fellow officer from Alaska and I jumped on the opportunity to

see if he wanted to eat with us. Lucky for us he was happy for the invite. We

had a great dinner... He’s actually a really cool and down to earth guy. He has

only been the Surgeon General for a couple months, so hopefully his new

position doesn’t change personality.

I had the privilege of meeting a former surgeon general as well,

Dr. Antonia Novello. Dr. Novello is a Puerto Rico native and as such, was on

the island to try and help where she could (side note, there was A LOT of

“important” people with connections trying to pull strings to help their family

and friends as much as possible). I met Dr. Novello when she came in to IRCT

asking to get assistance with something. Apparently, she didn’t like the answer

she was given, and I was in the path of her wrath. Luckily, I charmed her and

we had a good conversation about the current situation in Puerto Rico. She left

happy with IRCT, but still upset with whatever answer she received prior to

talking to me. The reason I tell you this is because I saw her a couple more

times over the course of the week, and she remembered my name (although I

forgot hers) and even kissed my cheek upon one of the greetings. I told

Danielle she better watch out because I got old Surgeon General’s hitting on

me. Side note – Dr. Novello is actually a convicted felon. Look it up!

Sickness in IRCT

Apparently, everyone that went to Puerto Rico to help out

eventually came down with allergy like symptoms with a border line sinus

infection differential. It was odd. Nobody really knew what it was or why, but

it seemed to impact everyone. Some people hypothesized that it could be the

intense amount of mold that is spreading on the island. Others thought that all

the downed trees and plants released their pollen while at the same time,

irritants and pollutants were stirred up. Whatever the cause, it resembled my

annual, spring allergy initiated sickness, and knocked me on my butt for a good

48 hours. Luckily, I packed a lot of good medications with me and I was able to

kick it.

The threat of sickness got to the point where they were sending

people home with known weaker immune systems. The poor air quality and moldy

environment throughout the island was a complication waiting to happen. There

were a couple people that were upset over the decision, but we didn’t want to

take our focus off the mission by having to care for people we brought to help

the mission (if avoidable).

Costs and Money

Things in Puerto Rico were naturally more expensive than the

states. It’s an island… items cost more on islands that have to ship them there

to be purchased. Unlike a typical disaster in the states, you can’t knock on

the neighbor state’s door and ask for ambulances, food/water, or other

resources. I say this because the emergency response really brought this to

light. With the combination of the isolation and expense of getting items, this

response effort will likely cost our nation BILLIONS of dollars. It will single

handedly be the most expensive natural disaster response in our nation’s

history.

And speaking of cost, very few places actually took credit cards

as payment. Due to connectivity being down in many places, credit cards had no

way of being processed. Cash was king (US Dollar). This posed problems for

responders who had government credit cards that needed to be used to acquire

resources. I think there will be a lot of reimbursements being paid as well.

Transportation

As I mentioned earlier, driving in Purto Rico was rough with no

traffic lights, debris, and bad drivers. In addition, 2/3 of the island was cut

off to driving due to the inability to drive on roads that were no longer there.

This meant getting supplies and responders to the other 2/3 of the island

relied heavily on air transportation, and slightly on boats. Helicopters (black

hawks) were the method of choice. The helos were flying around the clock,

dropping items, picking up patients, supplying nourishment, returning

responders. For an island of 3.5 million people, even nonstop helicopters can’t

possibly keep up with the demand of 2/3 of the population.

Small planes were good for runways that were clear enough to

accept them. On about the second day of the deployment, there was a small plane

accident on the strip right next to the convention center. A handful of people

in IRCT witnessed the crash as well. I never heard what the outcome of the crash

was or if there were any injuries or fatalities.

Flying in and out of the island was difficult too (mentioned

elsewhere here). Luckily IRCT landed a charter plane that would fly to and from

Atlanta on Monday and Thursdays. Commercial flights into the island were easy

to book, but off the island proved difficult due to the number of people that

wanted to leave.

Unprofessional Encounters

I met many people during the deployment, but the one person that

stood out the most was a girl I will rename as Jill. Jill was in IRCT. She was

not the typical incident command personal. She was tall, had long blond hair,

big chested, extremely muscular, and she wore a bright red t-shirt everyday

with the sleeves rolled up (everyone else was in a specific uniform). Apparently,

she was a kick boxer and owned a consulting company where she teaches different

nations how to prepare for emergency responses. Jill was assigned as a section

lead in Operations. The reason she is so memorable is not only because she

physically stood out, she had a personality that made her extremely unique.

Jill was a distraction. She was extremely unprofessional, rude,

attention seeking, had a my-way-or-the-highway attitude, belittled and bullied

people, was very loud, loved attention from guys, and overall thought she was

some hot $H!T. She annoyed me from day one. I couldn’t believe she was allowed

in IRCT, let alone allowed to act like that. The thing that made her behavior

worse as the days went on was that nobody said anything to her the entire time,

thus enabling her. She didn’t just annoy me, many people were uncomfortable by

her presence and apparent uninhibited reign over people.

One day she yelled across the room to try and get my attention.

She asked me something and my response wasn’t the answer she wanted. Seeing

that I disagreed with her in front of her influential peers, she retracted to

her aggressive, bullying tactics to get me on the same page as her. Jokingly,

she pulled out a switch knife, walked across the room at me and mentioned that

she would cut me. Now, this act wasn’t received by me as aggressive and I was

never scared of her actually using the knife. I know it was her way of aggressively

kidding around, however, no matter what the situation, this type of behavior is

absolutely unacceptable.

Shortly after, I asked my service chief how I file a formal

complaint. She asked me what I wanted to report. After telling her about the

encounter with Jill, she immediately told me to send her an email with the

details and she would make sure Jill was on the charter flight back home that

left the next day. That is exactly what happened too.

USNS Comfort

If you do not know what the USNS Comfort is, check out this link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USNS_Comfort_(T-AH-20)

The comfort arrived in Puerto Rico while I was there. It was

immediately utilized and functioned as the referral facility for complicated

cases and the receiving hospital for any facility that had to emergently

evacuate. This actually happened shortly after it arrived too. A functional

hospital lost all generator power and they had to transport all patient as fast

as they could, including those on ventilators and lifesaving equipment.

Another Hurricane

Hurricane Nathan decided to throw a curve ball into the mix. This

hurricane started along the east coast of Mexico and was headed through the

gulf directly at Louisiana and Florida and through to Georgia. We had to send a

few IRCT folks home to protect their homes ahead of this hurricane. We were

also worried that it would shut down our Atlanta operations for a little bit,

and thus delay our charter flights coming in and out of Atlanta. Luckily the

hurricane fizzled out and didn’t hit the US too hard to impact operations in

Puerto Rico (or damage the states).

Any End?

The withdrawal of our resources is going to be difficult in Puerto

Rico. Yes the devastation was massive, however, there is a questionable

baseline status for the infrastructure and medical system. Puerto Rico claimed

bankruptcy in May and as such, has little to no resources to contribute. The

medical system in Puerto Rico is dismal. All good providers have been driven

out of the country. The combination of all of this is where the withdrawal of

responders will be difficult.

How do you remove an efficient system of medical care (although

meant for short term) that would result in people suffering and dying? Is this

OK if that level of suffering and dying is the same level it was before the

hurricane met? Even though that level is inappropriate and below the standard

we are accustomed to meeting and handing off? How can you measure that level?

That is the problem we will face with withdrawing. Medical care

will be worse upon responders leaving, but few know and understand how it was

prior to the hurricanes. Of course, the local government and media will likely spin

it like we withdrew too early and don’t care about Puerto Rico, but that’s the

nature of the beast when it comes to disaster response in some areas.

Furthermore, all the focus is on Puerto Rico and the Virgin

Islands. Imagine what the other islands in the Caribbean are like… and they

don’t have a resource like the United States to come and help them.

Returning Home

Leaving Puerto Rico was difficult due to commercial flights being

completely sold out. The charter only left twice a week. As a result, many

people either had to leave after or before their orders expired (I was a couple

days beyond). The other thing about the charter flight was that it worked well

for IRCT’s priority of ensuring good mental health of the responders. A welcome committee was on the runway to

welcome us back home. Unfortunately, a “recovery” day in Atlanta was mandated

for all responders leaving Puerto Rico. We were all required to participate in

a group debrief, information sharing, and mental health counseling session the

day we arrived. A couple responders had to be emergently demobilized and escorted

home due to suicidal/ homicidal tendencies.

The 24 hour hold over initiative was good in thought, but it upset

a lot of people who would rather relax at home than in some random hotel. I was

not happy about it because my itinerary was scheduled to leave Atlanta very

late the next day. Traveling for 12 hours and losing four to time zones just

didn’t make sense to have me travel so late when I could spend the day doing

this. I asked for an exception and it was granted, resulting in a new itinerary

to travel during the next day instead of night.

Randoms

Here are a bunch of random things that happened that I don’t have

enough content to make its own section… There were bats everywhere at night; I

was shocked to see so many iguanas, which in fact are allowed to be hunted now

on the island because there are so many; there were only two washing machines

in the hotel and they didn’t work good (I finally got to use them on my last

day there, I had to wear a wet/hot uniform home); the AC was not turned on in

the plane during the two hour boarding process (like sitting in a parked car

with windows up).

Here are a couple things that happened that I can’t go into

details about… we were overseeing a 250 bed hospital with 500 patients in it;

the highest nurse to patient ratio at a facility was 18 to 1; an entire

hospital lost power and had to be evacuated within three hours; IRCT had to go

on lockdown a couple nights due to security concerns; a cholera outbreak

occurred; flooding happened with every rain including hospitals, medical

stations, and the convention center where all the hundreds of people were

staying on cots; we depleted the supply of water for helo drops a couple times;

dams were failing and the Army Corps of Engineers were here to address; power

outages/ surges occurred daily; dead bodies were stacking up thick (not because

of the hurricane, but because of the normal death rate and no place to put

them); I heard “I Heard” at least a thousand times.

Pics and News

Not many people knew I deployed to Puerto Rico. Prior to

deployment, I was instructed to not make my whereabouts known for security

purposes, especially on Facebook. Along the same lines, I was told to stay off

social media and avoid taking pictures. I didn't ask questions, I just followed

orders. I later find out this same message wasn't relayed to everyone. I

continue to see many officers posting statuses and pictures on Facebook.

Our charter plane to Puerto Rico.

All aboard!

Puerto Rico from above.

Standing buildings in San Juan.

Is it safe to deplane on the tarmac and just stand there without anyone telling us what we can and can't do, and where we can and can't go?

The transportation method of choice on the island.

This is the brains of the medical missions... IRCT.

Commander Frank Verni, Vice Admiral Jerome Adams (the Surgeon General), and me

You can't really see it, but this is the line that circled the parking lot of the grocery store next to the hotel every morning.

Rescue animals being evacuated.

This is the Samaritan's Purse cargo plane. It was HUGE. Look them up!

The Pent House floor of our hotel... gutted from rain damage.

Here is an example of a $5 breakfast. This is four bites for me :)

Luxurious cots many responders had to sleep on.

Line 'em up.

This is one of three receiving docks. It contained about 500 claimed cots.

Initial briefings upon arrival to the Convention Center.

A flooded and totaled hospital.

More water damage.

Trees no longer had leaves or fruit. This is part of what's left of the rain forest.

More examples of the bare shrubbery.

The USNS Comfort at dock.

One of a few shots aboard the USNS Comfort... bunk patient beds.

Typical field, tent accommodations for medical teams.

Inside a portable, federal medical station.

If a building didn't have roof damage or leaking, it was extremely fortunate.

The fueling station never slept.

Me briefing new arrivals.

The outside of a federal medical station.

Multiple federal medical station tents.

Generator power.

Water bladders.

A Colosseum we converted into an acute and chronic care facility.

US Health and Human Services Video Updates: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLrl7E8KABz1HiKK08T2Lu6X3xSSny9C4z

US Health and Human Services News Releases: https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/hurricane-response/index.html

FEMA Video Updates: https://www.youtube.com/user/FEMA/videos?view=0&flow=grid&sort=dd

** FINAL NOTE - I would like to reiterate how huge this disaster is/was. I am not pointing fingers, judging, or placing blame on anyone for the inefficiencies, or causes of frustration I voiced. I want everyone to understand that in any situation you prepare for, there is always a saturation point for how something can be handled. Puerto Rico's magnitude initially exceeded this, and that is when things start falling between the cracks. This will be a great learning experience because we learn the best when we face something for the first time, especially from the failures that occur. Then, we hope that something this large doesn't happen again.

Also, it feels awkward when people thank me for the service and helping in Puerto Rico. My goal isn't to receive that praise, it is merely to share my experience. I understand their sentiment and appreciate it, but similar to staying in the hotel in San Juan, I feel undeserving. I say that because I am forever in debt to our armed brothers and sisters that risk their lives fighting for and protecting our freedom. I am proud to serve our country in times of need, but my service is dwarfed in comparison. I am forever humbled and more in debt to their greater sacrifices. **